Porting a Windows Phone app to iOS

Yes, I know. It’s not the most common direction. Creating an app first on Windows Phone, and then porting it to iOS?

In my spare time I recently created and released a Windows Phone app that synchronizes your Google Chrome environment to Windows Phone, to access your Chrome bookmarks, passwords, recently viewed web pages, and (experimentally) open tabs from Windows Phone.

It does this by talking the Chrome sync protocol directly to Google’s servers just like Chrome itself does.

I created the app by downloading the Chromium source code, and then building and running Chrome on my PC (Chrome is written in C), working out how it did the synchronization, and then I did the same thing from C# in my Windows Phone app.

I released the app and it was well received.

The next step in my master-plan was to release a similar app for the iPhone and iPad, by porting my app using MonoTouch to iOS. I got to the point where it was working, and then, well … Google released Chrome for iOS … at which point the potential audience for my iOS product shrank to approximately zero.

Nevertheless I did get to port an app from Windows Phone to iOS using MonoTouch; I thought I’d share my experience.

I’m going to:

- Explain how I set up my development environment to run Visual Studio on my Mac, with just a three-finger swipe to go between Visual Studio and the real-device debugger;

- Describe how I structured my project to share code between the two apps;

- Explain how I implemented different database access code, hidden behind a common interface;

- Look at a significant hurdle I hit where my code ran fine in the iPhone Simulator, but crashed and burned on a real device, and what I did to resolve this;

- Reflect on the overall experience.

About MonoTouch

First a word about MonoTouch. If you are like me, you hate the idea of a porting framework because you want to create an app that has a native look and feel … not some generic bland UI that looks the same on all platforms, and is thus horrible on all platforms.

Here is what you need to know about MonoTouch: it provides C# bindings to the native iOS frameworks. It does not provide any UI compatibility layer to let you run Silverlight on iOS. You still design your UI using NIB files, create outlets, ViewControllers etc. You use MonoTouch to create a native app, that is indistinguishable from an app coded in Objective C.

So if you can’t port the UI, what is the point? It turned out that most of the challenging code in my app was the backend stuff – authenticating, syncing, storing in the DB, etc. The UI was pretty straightforward. I wanted to port the backend code, but put an authentic iOS UI on it.

Learning iOS and MonoTouch

A few years ago Red Gate software acquired a product I created and consequently am a Friend of Red Gate. One of the perks was a free years subscription to the online video course company, Pluralsight.

Before doing anything with MonoTouch I watched the available Pluralsight courses on iOS and MonoTouch. On most devices, such as the iPad you can watch them at 1.5x or even 2x the normal speed. I found these courses to be excellent, and I now pay out of my own pocket to subscribe.

The half-life of the information gleaned through watching these videos is very short in my brain, so I needed to get my hands dirty very quickly after watching the videos.

Setting up the development environment

Although I did not know much about MonoTouch development, I did know that I wanted to continue using Visual Studio, and more specifically the Resharper development/refactoring tool from Jetbrains: .NET development without Resharper is unthinkable for me.

One other thing I knew was that I didn’t want to fork over US$200 for a MonoTouch license without being sure that what I wanted to do would work. Fortunately you can download and use MonoTouch for free, but you can only deploy apps to the iOS Simulator – not to real devices. This seemed good enough to me. I thought that if it worked on the emulator, it was very likely to work on a real device.

Little did I know how naïve I was.

Windows on Mac

I already had a MacBook Air running OS X, and Parallels hosting Windows 7. I also already had Visual Studio installed within Windows 7 and Resharper installed.

MonoTouch

I downloaded and installed MonoTouch on the OS X environment, and made sure I could build and run a simple project. Then I followed the instructions in this email to set up my Windows and Visual Studio environment to be able to edit MonoTouch projects.

Visual Studio and MonoTouch together

I’ve read a lot of stuff about people using Dropbox to automatically synchronize their PC based Visual Studio with their Mac based MonoTouch. Instead what I did was simply to open the MonoTouch solution from within Visual Studio running in the virtual machine on the same PC, using the ability to open the host OS’s files within the VM.

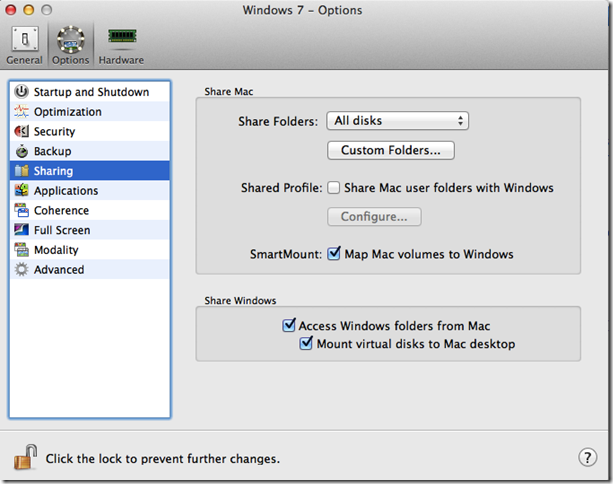

I set up the Mac’s file system to be available inside Windows:

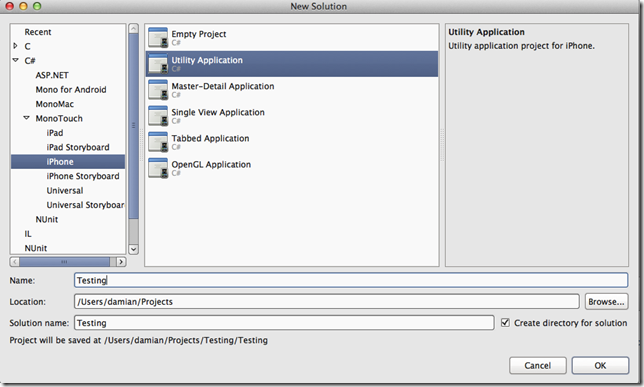

I created a new solution using MonoDevelop on MacOS:

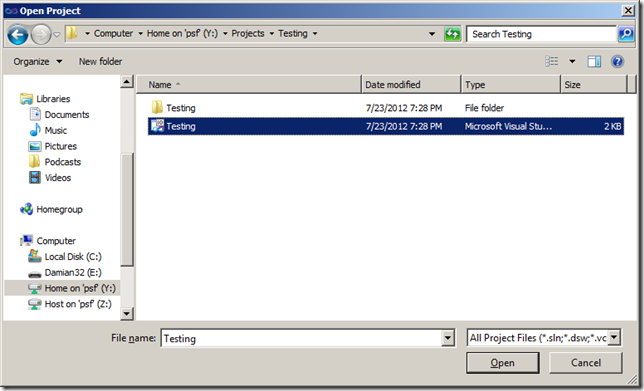

Then I opened that solution using Visual Studio running in the parallels Virtual Machine, via the Mac’s drive mounted in the Windows Virtual Machine (notice the drive on the left hand side):

I ended up being able to edit and build using Visual Studio, then use a four-finger swipe on the mousepad to switch back to MonoTouch to run and debug the app. Here is a quick video of the complete edit, debug run cycle using MonoDevelop to run the app under an iPhone simulator on iOS, and Visual Studio to develop:

Using Visual Studio to develop, and then MonoTouch to deploy and debug was almost totally painless. I still needed to learn MonoTouch’s debugger shortcuts, but that was the only pain-point.

Porting the code

The Windows Phone project structure

The original version of the Windows Phone project was not designed with the idea of porting it to iOS, however I did use the standard MVVM pattern, which meant that my sync logic and database code was totally decoupled from my UI code.

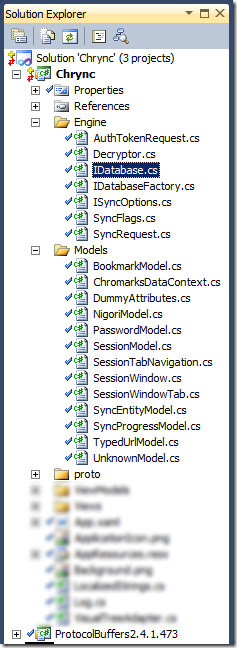

I used two different Visual Studio solutions, however the iOS solution references the same source control folders as the Windows Phone Solution for the shared classes. These are the classes that are shared between the solutions:

The Engine namespace contains the classes used to talk the Chrome sync protocol to Google’s servers. The Models namespace contains the classes used to represent entities written to, and read from the database. The proto folder contains protocol-buffer definitions and generated classes, and the ProtocolBuffers folder contains the engine used to talk the protocol buffers protocol. All of these classes are shared between the Windows Phone and iOS versions of the app.

Almost all my non-UI code could be reused between Windows Phone 7, and iOS, however there were a couple of areas where I needed to re-write code, namely storage of Settings, and Database code, which I hide behind interfaces (see IDatabase, IDatabaseFactory, and ISyncOptions in the picture above).

Database access across platforms

Although I love using LINQ, Microsoft’s recent announcement that Windows Phone 8 will support SQLite was very welcome, since if I’d used SQLite on Windows Phone, my database code would have remained unchanged. For this app, I ended up re-writing the database read/write code, with different implementations of an IDatabase interface used by the sync engine.

I use LINQ to SQL as my database implementation on Windows Phone, and I wanted to re-use the same database entities on iOS, even if they were stored using a different technology, namely SQLite. I ended up using #IFs to allow me to use the same classes between both iOS and Windows Phone.

I’m not going to go into all the details of what I did, but I thought I’d give you a flavour by looking at the class used to represent encryption keys exchanged during synchronization. I’ll show an extract of the class itself, and then the two different IDatabase implementations which read/write instances of these classes.

Shared database entity class

This is an example of the NigoriModel class, used to represent encryption keys. Note the #IFs used for Windows Phone specific classes. You’ll also see that I have not commented out the use of the Table and Column attributes – I simply defined my own TableAttribute class, #IFd to be only visible when building for iOS.

I used the Windows Phone ProtectedData class to encrypt sensitive information prior to committing it to the database.

using System;

using System.ComponentModel;

#if WINDOWS_PHONE

using System.Data.Linq;

using System.Data.Linq.Mapping;

using System.Security.Cryptography;

#endif

namespace Chromarks.Models {

[Table]

public class NigoriModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

#if WINDOWS_PHONE

, INotifyPropertyChanging

#endif

{

private int _id;

[Column(IsPrimaryKey = true, IsDbGenerated = true, DbType = "INT NOT NULL Identity",

CanBeNull = false, AutoSync = AutoSync.OnInsert)]

public int Id

{

get

{

return _id;

}

set

{

if (_id != value)

{

NotifyPropertyChanging("Id");

_id = value;

NotifyPropertyChanged("Id");

}

}

}

private byte[] _userKeyEncrypted;

[Column]

public byte[] UserKeyEncrypted

{

get { return _userKeyEncrypted; }

set

{

if (_userKeyEncrypted != value)

{

NotifyPropertyChanging("UserKeyEncrypted");

_userKeyEncrypted = value;

NotifyPropertyChanged("UserKeyEncrypted");

}

}

}

private static byte[] Encrypt(byte[] plain) {

byte[] bytes = null;

#if WINDOWS_PHONE

bytes = ProtectedData.Protect(plain, null);

#else

bytes = plain; // TODO: implement for iOS

#endif

return bytes;

}

public byte[] UserKey

{

get { return Decrypt(UserKeyEncrypted); }

set {

UserKeyEncrypted = Encrypt(value);

}

}

...

// Version column aids update performance.

#if WINDOWS_PHONE

[Column(IsVersion = true)]

private Binary _sqlVersion;

#endif

#region INotifyPropertyChanged Members

public event PropertyChangedEventHandler PropertyChanged;

// Used to notify the page that a data context property changed

protected void NotifyPropertyChanged(string propertyName)

{

if (PropertyChanged != null)

{

PropertyChanged(this, new PropertyChangedEventArgs(propertyName));

}

}

#endregion

#region INotifyPropertyChanging Members

#if WINDOWS_PHONE

public event PropertyChangingEventHandler PropertyChanging;

#endif

// Used to notify the data context that a data context property is about to change

protected void NotifyPropertyChanging(string propertyName)

{

#if WINDOWS_PHONE

if (PropertyChanging != null)

{

PropertyChanging(this, new PropertyChangingEventArgs(propertyName));

}

#endif

}

#endregion

}

}

In this way I was able to use the same classes in my synchronization engine, whether running on iOS or Windows Phone. Since all database access was hidden behind the IDatabase interface, all I needed to do was provide the sync engine with different IDatabase implementations depending on the platform:

Windows Phone 7 IDatabase implementation (LINQ to SQL)

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.Linq;

using Chromarks.Engine;

using Chromarks.Models;

namespace Chromarks.ViewModels

{

class DatabaseImpl : IDatabase {

private const String Tag = "DatabaseImpl";

private readonly ChromarksDataContext _dataContext;

public DatabaseImpl(ChromarksDataContext dataContext)

{

_dataContext = dataContext;

}

public void Dispose()

{

_dataContext.Dispose();

}

public void SubmitChanges()

{

_dataContext.SubmitChanges();

}

public bool AnySyncProgress()

{

return _dataContext.SyncProgress.Any();

}

public NigoriModel GetNigoriWithName(string keyName)

{

try

{

return _dataContext.Nigoris.SingleOrDefault(n => n.KeyName == keyName);

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Log.Error(Tag, "Error invoking GetNigoriWithName with " + keyName, ex);

return null;

}

}

public void InsertNigori(NigoriModel nigori)

{

_dataContext.Nigoris.InsertOnSubmit(nigori);

}

...

iOS IDatabase implementation (SQLite)

I replicated the Windows Phone behaviour in the iOS implementation, using equivalent mechanisms from SQLite.

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Data;

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.IO;

using System.Text;

using Chromarks.Engine;

using Chromarks.Models;

using Mono.Data.Sqlite;

using sync_pb;

// ReSharper disable CheckNamespace

namespace Chromarks {

// ReSharper restore CheckNamespace

internal class Database : IDatabase {

private readonly SqliteConnection _connection;

private SqliteTransaction _transaction;

private bool _disposed;

internal Database()

{

_connection = GetConnection();

_connection.Open();

}

public void Dispose()

{

Debug.Assert(!_disposed);

_disposed = true;

if(_transaction != null) {

_transaction.Rollback();

_transaction = null;

}

_connection.Dispose();

}

public void SubmitChanges()

{

Debug.Assert(!_disposed);

if (_transaction != null) {

_transaction.Commit();

_transaction = null;

}

}

public bool AnySyncProgress()

{

Debug.Assert(!_disposed);

using (var cmd = _connection.CreateCommand())

{

cmd.CommandType = CommandType.Text;

cmd.CommandText = "select COUNT(*) FROM SyncProgressModel;";

var count = (long)cmd.ExecuteScalar();

return count > 0;

}

}

public NigoriModel GetNigoriWithName(string keyName)

{

Debug.Assert(!_disposed);

using (var cmd = _connection.CreateCommand())

{

cmd.CommandType = CommandType.Text;

cmd.CommandText =

@"SELECT [UserKeyEncrypted], [MacKeyEncrypted], [EncryptionKeyEncrypted] FROM [NigoriModel] WHERE " +

"[KeyName] = @KeyName";

Log.Debug("Database", cmd.CommandText);

AddParameter(cmd, "@KeyName", keyName);

using (var reader = cmd.ExecuteReader())

{

if (!reader.Read())

{

return null;

}

var result = new NigoriModel

{

UserKeyEncrypted = (byte[])reader["UserKeyEncrypted"],

MacKeyEncrypted = (byte[])reader["MacKeyEncrypted"],

EncryptionKeyEncrypted = (byte[])reader["EncryptionKeyEncrypted"],

};

return result;

}

}

}

public void InsertNigori(NigoriModel nigori)

{

Debug.Assert(!_disposed);

using (var cmd = _connection.CreateCommand())

{

cmd.CommandType = CommandType.Text;

cmd.CommandText =

@"INSERT INTO [NigoriModel] ([KeyName],[UserKeyEncrypted],[MacKeyEncrypted],[EncryptionKeyEncrypted])" +

"VALUES (@KeyName, @UserKeyEncrypted, @MacKeyEncrypted, @EncryptionKeyEncrypted);";

Log.Debug("Database", cmd.CommandText);

AddParameter(cmd, "@KeyName", nigori.KeyName);

AddParameter(cmd, "@UserKeyEncrypted", nigori.UserKeyEncrypted);

AddParameter(cmd, "@MacKeyEncrypted", nigori.MacKeyEncrypted);

AddParameter(cmd, "@EncryptionKeyEncrypted", nigori.EncryptionKeyEncrypted);

cmd.ExecuteNonQuery();

}

}

...

Running the app

The iOS Simulator

I was amazed and delighted to find that all the networking code just compiled and ran using MonoTouch.

Once I got the database implementation working on iOS, I ran a simple iOS app using my Chrome sync email address, password and application-specific password (I have that option turned on for my account). It worked – I was able to communicate to Google’s servers and dump out my synchronized bookmarks.

A real device

So far this was all done using the iOS emulator, but I was on a high – I took out my credit card and paid to buy a license to use MonoTouch on physical devices instead of just virtual devices. I also paid to become a registered Apple iOS developer. There are very thorough instructions on how to set up your real-world iPhone as a developer device.

I rushed through the setup instructions, deployed my app to the iPhone, ran it and … it crashed. The same code that had run fine on the emulator failed on the real device.

Generic Functions – the problem

Turns out I should have read those warnings and release notes, rather than just diving in. One of the restrictions that MonoTouch faces is that it can not dynamically generate code at runtime, and one of the C# constructs that requires this generic functions. And guess what, the protocol buffers code made liberal use of generic functions, such as this:

/// <summary>

/// Reads an enum field value from the stream. If the enum is valid for type T,

/// then the ref value is set and it returns true. Otherwise the unkown output

/// value is set and this method returns false.

/// </summary>

[CLSCompliant(false)]

public bool ReadEnum<T>(ref T value, out object unknown)

where T : struct, IComparable, IFormattable, IConvertible

{

int number = (int)ReadRawVarint32();

if (Enum.IsDefined(typeof(T), number))

{

unknown = null;

value = (T)(object)number;

return true;

}

unknown = number;

return false;

}

Generic Functions – the solution

I wrote new functions to be non-generic:

public bool ReadEnumNonGeneric(Func<object, bool> isEnum, Action<int> setEnum,

Action<object> setUnknown)

{

int number = (int)ReadRawVarint32();

if (isEnum(number)) {

setUnknown(null);

setEnum(number);

return true;

}

setUnknown(number);

return false;

}

… and changed the calling code to invoke my non-generic functions:

// if(input.ReadEnum(ref result.deviceType_, out unknown)) {

if (input.ReadEnumNonGeneric(n => Enum.IsDefined(typeof(global::sync_pb.SessionHeader.Types.DeviceType), n),

n => result.deviceType_ = (global::sync_pb.SessionHeader.Types.DeviceType)n,

u => unknown = u))

Now my code not only compiled, but it also ran!

MonoTouch compiler crash – not a problem

One issue that I never got to the bottom of is that the MonoTouch compiler crashed when compiling my code. My solution was to always compile under Windows, and then let MonoTouch transform the compiled code into an iOS app, and run it. I suspect that it is the fact that I left the generic functions there that causes the MonoTouch compiler to crash.

Conclusion

Although Google cold-heartedly destroyed my ambitions to release a Chrome-syncing app for iOS when they released Chrome, I still got a lot out of the experience of porting my app from Windows Phone, and I’m ready now for the next one.

Here are some final thoughts.

- Being able to program in C#, and having a lot of the .NET framework library available is fantastic if you are an experienced .NET programmer

- You’ll still need to invest significant effort into familiarizing yourself with the iOS programming frameworks, especially the UI to provide a truly native experience

- There are restrictions to the magic that MonoTouch can do - When your app works on the Simulator but not on the real device, don’t despair – read the FM and re-write your code to work around the restrictions. Better yet, read about the restrictions before you code.

- Its worth investing in getting your development environment set up properly – it was a joy to be able to edit, refactor, build in Visual Studio and then just swipe Visual Studio out of the way and run and debug the app, all on the same MacBook Air