From C# to Swift: some hints for those considering this path

I’m trying to convince myself that I’ve not really moved to Swift from C#, more that I’ve added Swift and SwiftUI to my repertoire, but I can feel my C# and .NET slipping away.

I can feel it. I can feel it. My C# is going. There is no question about it. I can feel it.

I thought I’d write a little helper for C# devs looking to pick up Swift, while I still have both in my mind.

My background

I’d been programming in C# since 2003, and used Xamarin to create and release cross-platform apps for iOS, watchOS, macOS, Android, WearOS, Windows, xBox and Tizen (yes really, that was me).

But Microsoft is not supporting the Apple Watch in their upcoming release of .NET, and that made me question everything. My main app targeted the Apple Watch, so I decided to learn Swift and SwiftUI.

Well over a year later, having released a non-trivial app to the App Store written in Swift and SwiftUI, and re-writtten another app in Swift using the upcoming async\await what can I share that might help someone else making the same journey?

The little things

I’ve been keeping a separate blog with small hints to myself at myswift.tips - mainly reminders to my future self as to I did something in the past.

Trivial things such as the lack of semicolons at the end of each line took some getting used to as did changing the order of the name and the type when declaring variables. It was surprising to me how quickly using lowercase letters at the start of method names became normal:

c#

int fred = 12;

int bloggs = 12;

string MyMethod(int x) {

return "hello world";

}

swift

var fred = 12

var bloggs: Int = 12

func myMethod(x: Int) -> String {

return "hello world"

}

Being expected to put parameter names at the call sites was natural, having been brought up that way programming in ADA early in my career:

myMethod(x: 12)

Swift does give you a way to not do this, and also a way to have a different external name and internal name:

func myMethod(outsideName insideName: Int, _ secondParameter: String) {

print(insideName)

}

myMethod(outsideName: 12, "hello")

guard

This looked alien to me as a C# developer:

swift

func hello(name: String, age: Int?) {

guard !name.isEmpty,

let age = age else {

return

}

print("Name: \(name) age: \(age)")

}

The guard is an inverted if … its condition must evaluate to true otherwise it must exit.

The age check above checks that age is not nil (swift’s equivalent to C#’s null),and assigns a new age variable if it is not, so that later age is an Int not an Int?

Also note how the comma can be used to separate the if’s clauses instead of &&.

Trailing closures

Some aspects of Swift closure system were trivial to pick up given C#’s lambdas, as well as the Func<…> and Action<…> system generics.

Nevertheless it took a moment to get used to being able to pass a closure as the last parameter to a method outside of the method’s brackets:

c#

void MyMethod(int x, Action callback) {

callback();

}

// Call MyMethod

MyMethod(12, () => Console.WriteLine("This the second parameter"));

swift

func myMethod(x: Int, callback: () -> Void) {

callback()

}

// Call myMethod passing trailing closure

myMethod(x: 12) {

print("This is the second parameter passed as a trailing closure")

}

I’d seen this in other languages, and on reflection I like it - it renders the call site less cluttered.

Defer vs finally

In C# you can guarantee that a block of code will be executed by using:

c#

try {

// do something

} finally {

Console.WriteLine("This code will always execute");

}

Swift does things differently using defer, which can be placed anywhere:

swift

defer {

print("This code will always execute")

}

// do something

I appreciated that I always knew to look at the end of the block for the C# finally clause, located at the same place as it would execute, whereas Swift’s defer clauses can be put anywhere …

On the other hand it is also nice to see right at the start of a function a declaration of exactly what will be executed when the function finishes, no matter what happens …

Protocols vs interfaces

At first blush Swift protocols map well to C# interfaces … other than having to conform to a protocol in Swift vs implementing an interface in C#.

What I wasn’t used to however, was being to retroactively make a class conform to a protocol, by using extensions on the class:

Imagine you’ve access to a class defined by a third party:

swift

class MyClass {

func myMethod() {

print("This is myMethod")

}

}

Later you have a really handy protocol that you’d like to use:

protocol MyProtocol {

func anotherMethod()

}

You can retroactively make the class conform to the protocol by extending it:

extension MyClass: MyProtocol {

func anotherMethod() {

print("This is anotherMethod")

}

}

Then you can use it as though it had always implemented the protocol

let x: MyProtocol = MyClass()

x.anotherMethod()

Extending interfaces, structs and classes is a big thing in Swift, and not something I was used to from the C# world.

Protocol oriented programming

I’ve not yet toggled the switch in my brain, but you should know that Protocol Oriented Programming is a big thing for some people in the Swift world. Watch this video from Apple’s World Wide Developer Conference (WWDC) for more.

This is not yet another enum

What could be more boring than an enum? Everyone knows them, they’ve been here at least since C was created. Swift’s syntax is a little different from C#, but you get the idea:

swift

enum MarthaWellsBooks {

case allSystemsRed

case artificialCondition

case rogueProtocol

case exitStrategy

case networkEffect

case fugitiveTelemetry

}

let book: MarthaWellsBooks = .allSystemsRed

let book2 = MarthaWellsBooks.networkEffect

Talking about C, do you remember C’s unions? Swift’s enums integrate unions! … each case can have associated data:

enum Media {

case book(pages: Int)

case movie(minutes: Int, title: String)

case audioBook(narrator: String)

}

let media1 = Media.movie(minutes:74, title: "Children of Men")

Extracting the data is a little tricker:

switch media1 {

case .book(pages: let pages):

print("Book: \(pages) pages")

default:

print("Something else")

}

You can also check if a variable is a specific enum using an somewhat convoluted if

if case let .movie(minutes,title) = media1 {

print("Movie: \(title)")

}

Structs everywhere

In C# my go-to type was always the class, whereas in Swift it is the struct. Perhaps with C#’s new records this is changing (although they are reference types). Swift has optimized structs to the point that there is very little overhead in their reuse.

I’m still not fully there in terms of defaulting to structs, but I’m trying!

SwiftUI

This could be a blog post by itself. Just a couple of small points.

In C# when LINQ was first announced we were amazed to see that although it looked completely different from code, it was actually syntactic sugar in the sense that these two LINQ statements are interchangeable:

c#

var r = from c in s where char.IsLetterOrDigit(c) orderby c select $"ch: {c}";

// Same as

var r = s.Where(c => char.IsLetterOrDigit(c)).OrderBy(c => c).Select(c => $"ch: {c}");

The same goes for SwiftUI. It is compiled and is actually code, using the trailing closure syntax I showed above, together with a ViewBuilders:

struct ContentView: View {

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text("Hello, world!")

}

}

}

// Same as

struct ContentView: View {

var body: some View {

VStack(content: {

Text("Hello, world!")

})

}

}

In WPF, Xamarin Forms, and yes, Silverlight you might bind to a ViewModel with a ViewModel like this (you’d normally use helpers to cut out the INotifyPropertyChanged cruft):

// The View Model

class ViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged {

public event PropertyChangedEventHandler PropertyChanged;

private String _name = "";

public string Name {

get => _name;

set {

_name = value;

OnPropertyChanged(nameof(Name));

}

}

protected virtual void OnPropertyChanged([CallerMemberName] string propertyName = null) {

PropertyChanged?.Invoke(this, new PropertyChangedEventArgs(propertyName));

}

}

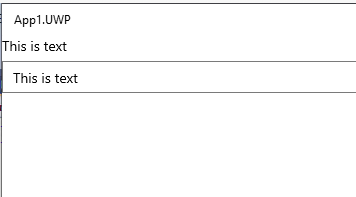

And the XAML like this

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8" ?>

<ContentPage xmlns="http://xamarin.com/schemas/2014/forms"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2009/xaml"

xmlns:app1="clr-namespace:App1;assembly=App1"

x:Class="App1.MainPage">

<ContentPage.BindingContext>

<app1:ViewModel/>

</ContentPage.BindingContext>

<StackLayout>

<Label Text="{Binding Name}"/>

<Entry Text="{Binding Name}"/>

</StackLayout>

</ContentPage>

As you type into the input field the label updates.

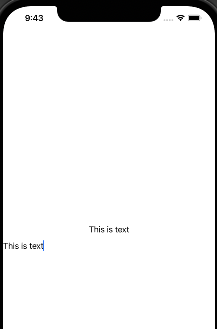

The equivalent in Swift and SwiftUI:

class ViewModel: ObservableObject {

@Published var name = ""

}

struct ContentView: View {

@StateObject var viewModel = ViewModel()

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text(viewModel.name)

TextField("Name:", text: $viewModel.name)

}

}

}

The @Published and @StateObject are Property Wrappers and they are doing a lot of the work here. In the .NET world we’ve spent forever trying to abstract away the INotifyPropertyChanged functionality that notifies views of changes to view models, whereas Swift and SwiftUI have cleaned it up.

There is so much more to say about SwiftUI, the most important of which is that views are functions of the view models, continuously regenerated as the view model changes.

It is a ridiculously powerful, exciting way to code, which can also be surprisingly flexible (look for a future post where I talk about implementing the Alexa Presentation Language in SwiftUI). It is also new (two years old), and it can be frustrating. But I believe it is the future.

The development environment

Moving to Xcode was a massive step back for me, coming from Visual Studio with Resharper installed. Refactoring is the main loss, as well as pro-active suggestions. I can’t tell you how many new C# features I learned when Resharper recommended changing my code to use those new features.

Nevertheless I do enjoy directly using Xcode to build and deploy apps, and the SwiftUI support is impressive, albeit occasionally buggy.

Its probably time for me to try out JetBrain’s AppCode iOS development tool.

Conclusions: Is it worth it?

Learning Swift and SwiftUI has broken my brain with new ways of thinking and new concepts, and in integrating these new ways of thinking into my mental toolbox I can’t help but feel that I’m a better developer because of it.

I still don’t want to believe I’m leaving .NET and C# behind, I could easily see myself going back to them, but only once I’ve truly mastered Swift and SwiftUI, which will be a challenge because they are evolving so fast.

By focusing on the Apple platforms I’ve lost the openness I had when I was shipping to many different platforms, but I’ve also gained something in that now I can go deep and that opens other possibilities such as creating an Alexa Presentation Language engine in SwiftUI.

Feedback

I’m at DamianMehers on Twitter, and may be available for consulting opportunities from December 2021 (DMs open). If you are looking to move an app from C# to Swift, or from Xamarin Forms to SwiftUI don’t hesitate to reach out.

Is there anything I should have covered? I didn’t talk about reference counting vs garbage collection for example. Perhaps a future post.

You can leave comments about this post here.